Poetry is a powerful form of expression that allows writers to share emotions, tell stories, and connect with readers on a deeper level.

Whether you’re just starting out or have years of experience, learning about the different types of poems can strengthen your skills and spark new inspiration.

In this guide, we’ll break down 12 key types of poems, explaining how they work, why they matter, and how you can use them in your own writing.

1. Haiku: The Art of Simplicity

The Haiku is one of the most recognizable forms of poetry, with roots in Japanese tradition. It’s known for its brevity: just three lines following a 5-7-5 syllable pattern.

Despite its short length, a well-written haiku captures a fleeting moment (often centered on nature or the changing seasons) with clarity and emotional impact.

Example:

An old silent pond…

Matsuo Basho

A frog jumps into the pond—

Splash! Silence again.

Why it works:

The Haiku’s minimalist structure challenges poets to express meaning in just a few carefully chosen words.

This constraint often results in striking imagery or emotion. It’s a great form for writers who value precision, clarity, and the art of saying more with less.

2. Sonnet: The Classic Love Poem

When most people think of poetry, the Sonnet is one of the first forms that comes to mind.

This 14-line poem follows a specific rhyme scheme and meter, and it was popularized by none other than William Shakespeare. There are two main types of sonnets: the Italian (also known as Petrarchan) and the English (or Shakespearean).

Example:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

William Shakespeare

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date…

Why it works:

The sonnet’s strict structure gives poets a framework to explore deep, often timeless themes like love, beauty, and the passage of time.

Working within its rhyme scheme and meter pushes writers to be deliberate with their language, which is why so many sonnets contain lines that stand the test of time.

3. Free Verse: Freedom of Expression

Free verse is the rebel of the poetry world.

Unlike traditional forms, it doesn’t follow a fixed rhyme scheme or meter, giving poets total freedom to shape their ideas however they choose. It’s a favorite among modern poets who prefer to break away from strict structures and let the content guide the form.

Example:

The fog comes

Carl Sandburg

on little cat feet.

It sits looking

over harbor and city

on silent haunches

and then moves on.

Why it works:

Free verse lets poets prioritize rhythm, tone, and natural flow over strict structure.

Without formal constraints, writers can experiment with language in bold, expressive ways — making this form especially appealing to modern readers and contemporary themes.

4. Limerick: A Touch of Humor

Limericks are short, humorous poems with a distinctive AABBA rhyme scheme.

Known for their light-hearted and often silly tone, limericks are a fun way to add humor and personality to your writing.

Example:

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Edward Lear

Who said, ‘It is just as I feared!—

Two Owls and a Hen,

Four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard!'

Why it works:

With its catchy rhythm and playful rhyme, the limerick is easy to remember and fun to share.

It’s a perfect match for writers who love clever wordplay and a good dose of wit.

5. Villanelle: The Power of Repetition

The villanelle is a 19-line poem built around repetition.

It’s made up of five tercets (three-line stanzas) followed by a final quatrain (four-line stanza). The first and third lines of the opening stanza are repeated throughout the poem in a specific pattern, creating a rhythmic, almost haunting musicality.

Example:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Dylan Thomas

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Why it works:

A villanelle’s repeating lines help drive home a central theme, making it especially powerful for exploring intense emotions or lingering thoughts.

The real challenge (and beauty) is writing refrains that stay impactful no matter how often they appear.

6. Ode: A Song of Praise

Odes are lyrical poems that celebrate a person, place, object, or idea.

Traditionally written in a formal style, they often speak directly to the subject with admiration and respect. This form is ideal for writers looking to express deep appreciation or reverence.

Example:

Ode to a Nightingale,

John Keats

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down…

Why it works:

With its elevated language and formal structure, the ode has a way of turning the ordinary into something extraordinary. It invites writers to reflect deeply and express their thoughts with richness and reverence.

7. Elegy: Poetry of Mourning

An elegy is a reflective, often somber poem that mourns the loss of a person, idea, or way of life.

Unlike more structured forms, elegies don’t follow a fixed format, giving poets the freedom to explore grief, memory, and mortality in a deeply personal way.

Example:

In Memory of W.B. Yeats,

W. H. Auden

Earth, receive an honored guest:

William Yeats is laid to rest.

Let this Irish vessel lie

Emptied of its poetry.

Why it works:

The elegy’s open structure gives poets space to express complex emotions without constraint.

It’s a powerful form for processing grief, inviting readers to step into the poet’s sorrow and reflect on loss alongside them.

8. Acrostic: Hidden Messages

Acrostic poems are distinctive because the first letter of each line spells out a word or message. While they’re often simple and playful, acrostics can also carry deeper meaning, especially when the chosen word or phrase holds personal significance.

Example:

Elizabeth it is in vain you say

Edgar Allan Poe

“Love not” — thou sayest it in so sweet a way:

In vain those words from thee or L.E.L.

Zantippe's talents had enforced so well:

Ah! if that language from thy heart arise,

Breath it less gently forth — and veil thine eyes.

Endymion, recollect, when Luna tried

To cure his love — was cured of all beside —

His follie — pride — and passion — for he died.

Why it works:

The acrostic’s built-in structure sparks creativity and encourages playful language.

It’s fun to write, satisfying to read, and especially useful for introducing beginners to the basics of poetry.

9. Epic: The Grand Narrative

Epic poems are lengthy narratives that recount the heroic journeys of larger-than-life figures.

These sweeping tales often feature gods, monsters, and legendary battles, capturing the values and myths of ancient cultures. Classics like The Iliad and The Odyssey have endured for centuries, preserving stories that helped shape entire civilizations.

Example:

Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus,

Homer, The Illiad

that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans.

Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades,

and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures…

Why it works:

The epic’s sweeping narrative gives poets room to tackle big themes like heroism, fate, and the human experience.

It’s a form that calls for both creativity and control, offering a rewarding challenge to those willing to take it on.

10. Ballad: The Storyteller's Song

Ballads are narrative poems that tell a story (often with musical roots).

They follow a regular meter and rhyme scheme, which makes them easy to remember and recite.

Common themes include love, loss, and folklore, brought to life through vivid imagery and strong emotion.

Example:

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

John Keats

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

Why it works:

With its steady rhythm and narrative drive, the ballad is perfect for poets who love telling stories.

Whether it’s a tale of love, loss, or mystery, this form draws readers in and carries them through the unfolding drama.

11. Sestina: A Complex Dance

The sestina is one of poetry’s most intricate forms, made up of six six-line stanzas followed by a three-line envoi.

What sets it apart is its unique pattern: the end words of the first stanza are reused in a rotating sequence throughout the poem, creating a spiral-like effect that challenges both writer and reader.

Example:

Miss Helen Slingsby was my maiden aunt,

T. S. Eliot

And lived in a small house near a fashionable square

Cared for by servants to the number of four.

Now when she died there was silence in heaven

And silence at her end of the street.

The shutters were drawn and the undertaker wiped his feet—

He was aware that this sort of thing had occurred before.

The dogs were handsomely provided for,

But shortly afterwards the parrot died too.

The Dresden clock continued ticking on the mantelpiece,

And the footman sat upon the dining-table

Holding the second housemaid on his knees—

Who had always been so careful while her mistress lived.

Why it works:

The sestina’s repeating end words create a sense of rhythm, continuity, and inevitability — perfect for themes like time, fate, or memory.

It’s a form that demands precision and patience, rewarding poets who enjoy structure with surprising emotional depth.

12. Concrete Poetry: Visual Art

Concrete poetry (also known as shape poetry) blends visual design with written word.

The layout of the text forms a shape that reflects the poem’s subject, turning the page into part of the poem’s meaning. It moves beyond traditional lines and stanzas, creating a visual experience as much as a literary one.

Example:

Imagine

a poem about

a tree where the

lines of text form

the shape of a tree, with

the trunk made of words and

the branches spreading out in

various directions. Each word and

line contributes to the overall image,

making the poem both a visual

and literary

experience.

Why it works:

Concrete poetry engages both the mind and the eye, turning the layout into part of the message.

It gives poets room to experiment with form and space — a creative challenge that can lead to striking, memorable results.

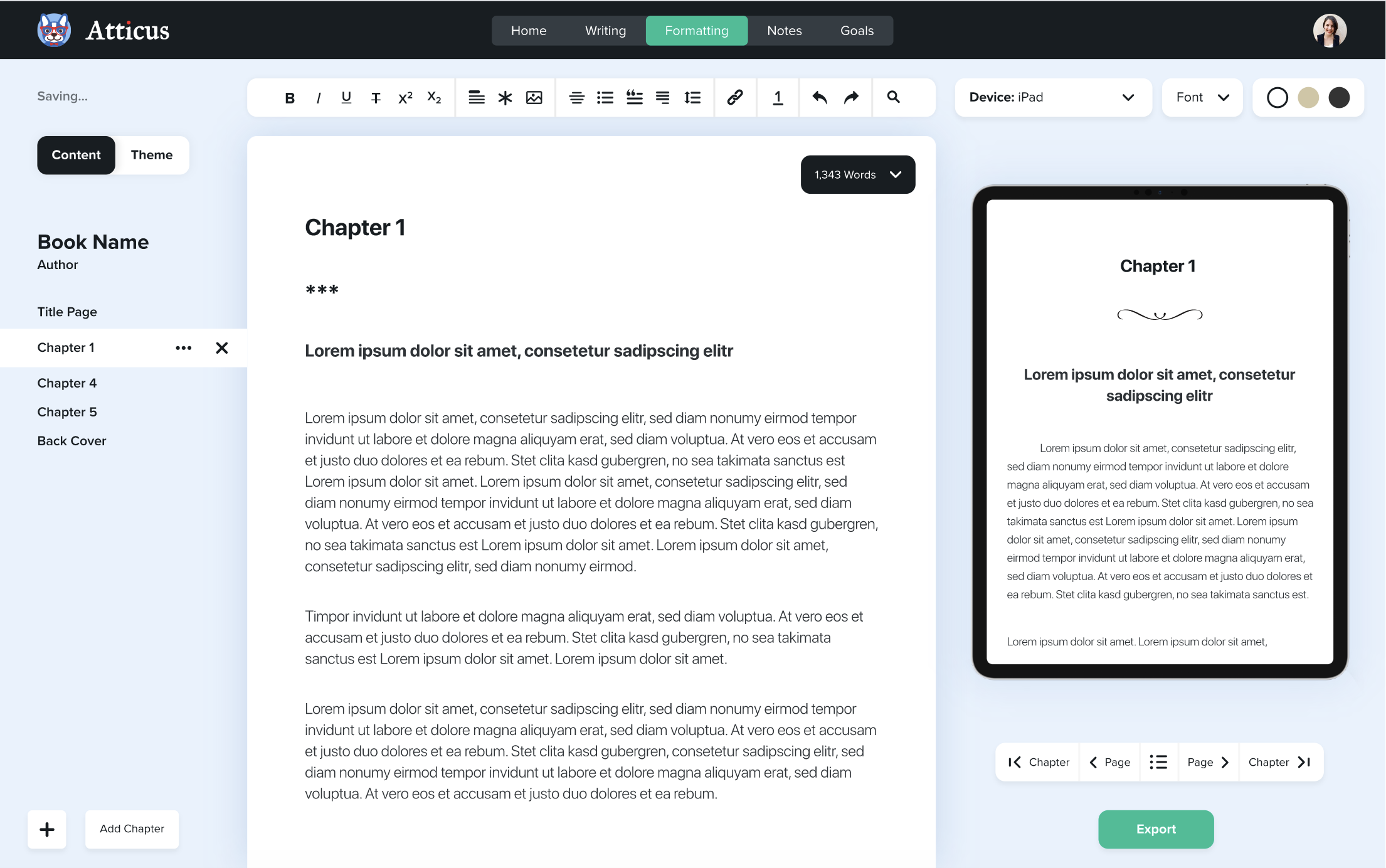

Integrating Poetry with Atticus

As you explore different types of poems, you may start thinking about how to organize them (or even publish your own poetry collection).

That’s where a tool like Atticus can make all the difference.

Format Beautiful Professional Books

Easy to use, and and full of amazing features, you can quickly turn your book into a professional book.

Check It OutAtticus is built for authors who want beautifully formatted books, whether you’re compiling sonnets, free verse, or shape-based poetry. It gives you full control over how each line, stanza, and visual element appears on the page.

With poetry-friendly features and an intuitive interface, Atticus lets you focus on your creative vision while it handles the formatting, making the publishing process simple, smooth, and stress-free.

FAQ

What is the most difficult type of poem to write?

The sestina is widely considered one of the most challenging forms. Its complex pattern of word repetition and rigid structure demand careful planning and a strong grasp of poetic technique.

Can I mix different types of poems in one collection?

Absolutely. Many poetry collections include a mix of forms — from haikus and sonnets to free verse — which keeps things engaging and highlights your range as a writer.

How do I choose the right form for my poem?

Start with your theme. Writing about love? A sonnet might fit. Something more introspective or spontaneous? Try free verse. Don’t be afraid to experiment. The best form is the one that helps your message land.

What tools can help me write and format my poetry?

Atticus is a great choice. It’s built to help poets format their work exactly as they envision it, making it easier to create professional-looking books with minimal hassle.

Do I need to follow all the rules of a poetic form exactly?

Not always. Traditional forms have guidelines for a reason, but many modern poets bend the rules to suit their voice or message. Understanding the form is key — once you know it well, you can choose when and how to break it for effect.

Is it okay to write poetry without rhyme?

Definitely. Rhyme can add rhythm and musicality, but it’s not a requirement. Many powerful poems — especially in free verse — use other tools like repetition, imagery, and line breaks to create impact.

How long should a poem be?

There’s no fixed length. Some forms, like haikus, are naturally short. Others, like epics, are much longer. Focus on the message you’re trying to convey — stop when you’ve said what needs to be said.

Types of Poems: Key takeaways

Exploring different types of poems opens the door to new creative possibilities.

Whether you’re drawn to the structure of a sonnet, the freedom of free verse, or the visual flair of concrete poetry, each form gives you a different way to express yourself.

The beauty of poetry lies not just in following the rules, but in learning how to bend, break, and reshape them into something uniquely your own.